Watercolours and Watercolour sketching

As many a water-colourist, I am self-taught. At the age of 13 years, I asked ‘Father Christmas’ for a big Roger’s box of 24 Winsor and Newton half-pan artist’s water colours: I tried to copy works by C. W. Tunnicliffe (1901–1979) and Robert Gillmor (1936). As you’ll read in other parts of this site my formal training as an artist and designer came much later. In the 1980’s I was lucky enough to be able to participate in master classes led by the late Eric Ennion and John Busby who both taught very me much about sketching (birds) in the field with watercolours.

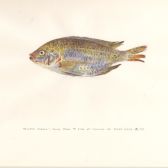

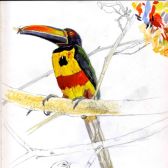

As you can see in my books, I often use a ‘dry’ technique, superposing transparent layers on top of a well-drawn and visible ‘skeleton’ of a drawing, thus making coloured sketches much in the same way as the 18th century tradition of academic studies which used transparent washes to colour ink drawings as in my studies of a Medlar , Fiery Billed Aracari or Telapia but the resemblance ends there as I use very advanced optical equipment to sketch wildlife (telescopes and ‘macroscopes’) and I’m often choosing non-ideal, ordinary or even quirky subjects as I find them in the field. I mostly choose my subjects for their poetic potential but I do not see watercolour sketches and quasi-scientific studies as scientific illustrations. If I depict plants from a plant community I will use hand-written text to explain points of scientific interest. In many cases there is a more or less conscious playing with this ambiguity: I want my watercolour studies to explore the poetry of the plants even if the objects were all collected within the same square metre in a quasi-scientific way!

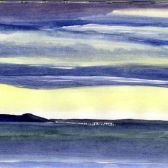

I am increasingly drawing in black ballpoint pen onto which I then add the coloured washes as in Achill Island. This makes for more luminous colours; as the fine black lines leave no carbon dust to ‘soften’ the colour especially when I use the Russian ‘White Nights’, Polish ‘Kaminski’ or French ‘Sennelier’, watercolours. Sometimes I will combine the thick black lines of calligraphic pens with colour for strong expressive graphic effects. Again more recently, I am tending to use higher concentrations of pigment and laying in colour quite wet – I’ve upgraded my loose-leaf blocks from 200gsm to 300gsm paper and I am also experimenting with medium sized formats of paper sheets on canvas (‘Marouflage’).

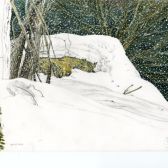

Recent intensive periods of watercolour sketching in the Camargue allowed me to use this technique more as well as perfecting the technique of leaving very fine areas of dry white paper (See: Between La Camargue et La Crau) - I’m afraid I never got into using masking fluid although I will add white for really complex effects i.e. in the case of rendering falling snowflakes. I used a combination of these techniques for the snow landscape Snowstorm of a neglected rice field terrace in the forest landscape in my book ASPARAGUS GREEN.

When I give watercolour classes or workshops many of the students are keen to learn techniques, the so called ‘tricks of the trade’. I don’t think there are many real secret formulas, short cuts or special techniques. In my opinion nothing beats hard graft, almost daily practice (the watercolour sketchbook is a great place for this), making many errors and not being afraid to experiment. Techniques and media are the tools of our trade and we should learn to know why we should use a given technique – we should master the technique and not vice-versa!

In my opinion this tendency to focalize on technique results in the neglect of so many other important aids essential to master watercolour. I recently visited a wonderful exhibition by the Luxembourgish water-colourist and architect, Sosthène Weiss (1872–1941) and by carefully analysing his paintings’ techniques; I was able to learn anew.

And if you can’t go to see real watercolours have a look at the many wonderful examples in good art history books: travel sketches by Albrecht Dürer, jellyfish by Charles Alexandre Lesuir, William Mallord Turner’s travel sketches and cathedrals and Watercolours by that other Architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Then there are the ‘one offs’ by famous oil painters: magnificent watercolours by Vincent Van Gogh or the watercolour ‘paintings’ by Emil Nolde and more recently a few rare ones by Lucien Freud and the wonderful pure wash sketchbooks by David Hockney.

One can meet many talented contemporary water-colourists at the major fairs and ‘Salons’: of travel ‘sketch-bookers’ at the Biennale of Clermont Ferrand (F) or the big watercolour fair at Namur (B). One can also learn much by looking at the illustrations in comic books or ‘Bande Déssiné’ and of course, in children’s books.

Not having learnt traditional calligraphy I apply my watercolour technique to the use of Indian ink and water to make my shadow paintings and don’t forget that painting in oils on canvas will sharpen your sense of COLOUR and this is (in my experience) a great help for colour use in watercolours. And perhaps most surprisingly of all if you try to write a short poem like a Haiku about what you are water colouring, the search for words will stimulate your visual memory and thus help to improve your picture!